Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer's Antique Auto and Farm Machinery Exhibit

Late 19th to Early 20th Century Corn Stalk Cutter

Following past information reported to the museum, we identify this item as a corn stalk cutter. According to the museum's source, Lambert J. Poels, this device was homemade, built around 1890. According to information recorded from Mr. Poels, "this machine is a homemade implement for cutting standing cornstalks, when a farmer could foresee no ear corn production from his field." Referred to by Mr. Poels as a "fodder sled," it "was a way to salvage the corn stalks for 'roughage'," that is, for feed or fodder for the farmer's livestock. The salvaged corn stalks were run through a feed grinder, or buhr mill, like the Letz mills in this exhibit, which ground the roughage into small pieces for livestock to eat. In some cases, farmers might have intentionally left parts of their fields unharvested, processing the entire plant, stalk and ear, for livestock feed.

c. 1930s De Laval No. 16 Cream Separator

This cream separator was made by the De Laval Cream Separator Company, headquartered in New York City. The mechanics behind this separator were first developed in the late 1800s by Gustaf De Laval in Stockholm, Sweden. Although several cream separators were made to be powered by an animal treadmill or an engine, this separator was made with a hand crank.

This cream separator has a very long series of patents:

195515, patented by W. C. L. Lefeldt and C. G. O. Lentsch on September 25, 1877, which you can view here;

247804, patented by Gustaf De Laval on October 4, 1881, here;

1212371, patented by Meredith Leitch on January 16, 1917, here;

1219567, patented by Meredith Leitch on March 20, 1917, which you can view here;

1253400, patented by Hans Olof Lindgren on January 15, 1918, which you can view here;

1256810 patented by Meredith Leitch and Bert Robert Wright on February 19, 1918, which you can view here;

1293082, patented by Charles Goebler on February 4, 1919, which you can view here;

1305813, patented by Meredith Leitch on June 3, 1919, which you can view here;

1316583, patented by Meredith Leitch on September 23, 1919, which you can view here;

1364119, patented by Meredith Leitch on January 4, 1921, which you can view here;

1364120, patented by Meredith Leitch on January 4, 1921, which you can view here;

1386122, patented by Meredith Leitch on August 2, 1921, which you can view here;

1386148, patented by Bert Robert Wright on August 2, 1921, which you can view here;

1407702, patented by Theodore H. Miller on February 28, 1922, which you can view here;

1407777, patented by Bert Robert Wright on February 28, 1922, which you can view here;

1409958, patented by Meredith Leitch on March 21, 1922, which you can view here;

1425664, patented by Meredith Leitch on August 15, 1922, which you can view here;

1431923, patented by Alton L. Baughman on October 17, 1922, which you can view here;

1453802, patented by Theodore H. Miller on May 1, 1923, which you can view here;

1476760, patented by Meredith Leitch on December 11, 1923, which you can view here;

1694468, patented by Vincent J. Gilmore on December 11, 1928, which you can view here;

1749764, patented by Erik August Forsberg on March 11, 1930, which you can view here;

1784953, patented by Bert Robert Wright on December 16, 1930, which you can view here;

1876656, patented by Erik August Forsberg on September 13, 1932, which you can view here;

1887315, patented by Hans Olof Lindgren on November 8, 1932, which you can view here;

1894985, patented by Alan E. Flowers on January 24, 1933, which you can view here; and

1905261, patented by Fredrik Bernstrom Seth on April 25, 1933, which you can view here.

Early 20th Century Gade 3 HP Engine

This air-cooled engine was manufactured by the Gade Brothers Manufacturing Company of Iowa Falls, Iowa. It was rated at 3 HP and has a 5" x 7" bore and stroke. According to a 1911 history of Hardin County, Iowa, the future Gade company was initially created by two men named Hardenrook and Rice. In 1903, Carl L. Gade joined these two men in the business. About six months later, Carl's brothers, Fred J., Willam H., and Louis A., replaced Hardenrook and Rice as co-owners. Over the next few years, the Gade brothers made a series of improvements to the company's engine, especially developing an air cooling system for their engines, and their company slowly grew. By 1914, the company had about 30,000 square feet of floor space, employed about 50 to 60 men, and had two traveling representatives. The Gade brothers' company not only shipped engines throughout the U.S., but also to other countries.

If you look at the top of this Gade engine, you might notice a small brass cup sticking up from the engine. This is a Lunkenheimer Brass Oil Cup made by the Lunkenheimer Company of Cincinnati, Ohio. This company was founded as the Cincinnati Brass Works in 1862 by Frederick Lunkenheimer, a German immigrant to the U.S. Over the first several years in business, Lunkenheimer made a wide variety of valves, lubricators, steam engine attachments, and other brass items. After Frederick's death in 1889, his son, Edmund, took over leadership of the company. Edmund was a very inventive person, obtaining several patents for valves and lubricators. In 1902, the company opened a new 150,000 square foot factory, employing about 700 workers. The factory produced items not only for the U.S. market, but for markets throughout the world. You can see a 1906 Lunkenheimer illustrated catalog, showing this brass cup and the company's other products by clicking or touching here.

|

| From the Lunkenheimer Factory 1906 Illustrated Catalog and Price List. Published in Cincinnati, Ohio. |

Notes

The information about the Gade company's 1903 formation is from Past and Present of Hardin County Iowa, edited by William J. Moir (Indianapolis: B. F. Bowen & Company, 1911), pp. 450-452. The information about the company in 1914 is from Farm Implement News, vol. XXXV, no. 48 (November 26, 1914), p. 70.

The information on the Lunkenheimer Company in 1902 is from Electrical World and Engineer, vol. XL, no. 18 (November 1, 1902).

1913 Rumely Type E 30-60 Tractor

This large tractor (serial #1719) was made by the M. Rumely Company in La Porte, Indiana. Weighing about 26,300 pounds, it was built with a 2-cylinder engine with a 10" x 12" bore and stroke, and was rated at 375 RPM. The M. Rumely Company and its successor, the Advance-Rumely Thresher Company, made 8,224 Type E tractors from 1910 to 1913 and from 1915 to 1923. The Type E's Nebraska Tractor Test was #8, performed from April 23rd to May 11th, 1920. You can view a pdf of the test results by clicking or touching here. If you would like to see a video of a Rumely Type E in action, click or touch here.

The M. Rumely Company, the predecessor to the Advance-Rumely Thresher Company, maker of five tractors and a steam engine in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit, had a long history before it built Stuhr Museum's Type E tractor. Like its successor, the M. Rumely Company's history can be traced back to 1848 and the migration of Meinrad Rumely from Germany to the United States. In that year, at the age of 25, Meinrad moved to Canton, Ohio, where his older brother, Jacob, lived. In 1850, he moved to nearby Massillon, Ohio, to join his brother, John, who was working for Russell & Company. Not long after moving to Massillon, Meinrad left for La Porte, Indiana, where he became a blacksmith in 1852. After his brother, John, joined him in La Porte, the two brothers created M. & J. Rumely Company. They made their first thresher by 1857 and their first steam stationary engine in 1861. Their products found a ready market.

In 1882, after adding portable and traction steam engines to their product lines, Meinrad bought out John’s portion of the company and renamed it M. Rumely Company. Meinrad’s company continued to grow during the last two decades of the 19th century, producing thousands of steam traction engines and other products. When Meinrad died on March 31, 1904, his two sons, William and Joseph, became the leaders of the company. Edward Rumely, Joseph’s son, also joined the company. By 1907, Edward took a leading role, guiding the company to even more products, especially to the development of a tractor that ran on a fuel other than steam. In 1907, he got in touch with John Secor, an engineer who had been experimenting with low-grade distillate fuels in internal-combustion engines. Meinrad had been familiar with Secor’s work in the 1880s, and Meinrad’s son, William, discussed Secor’s work with Edward as they talked about the work of Rudolf Diesel.

When Edward Rumely and John Secor discussed development of a tractor with an internal-combustion engine, Secor decided to join the company. When Secor joined Rumely so too did Secor’s nephew, William Higgins. Higgins, an inventor himself, had been working on a kerosene carburetor, patenting his invention with the help of his uncle. For a reported $213,000 in stock, Rumely obtained these two inventive minds and their patents. With the addition of Secor and Higgins, the company began working on what would become the famous OilPull series of tractors. After testing the first two-cylinder kerosene-fueled engines in 1909, the M. Rumely Company began production of their first OilPulls in 1910. Although the shop crew referred to the tractor as Kerosene Annie, Edward Rumely and his secretary came up with the name OilPull. On February 21, the La Porte factory finished the first OilPull, a Type B 25-45, weighing about 24,000 pounds. Before the end of the year, the factory had completed its first 100 OilPulls.

Building on the company’s continued success, Edward decided to expand through acquisition. In October 1911, Rumely bought the Advance Thresher Company of Battle Creek, Michigan. At about the same time, Rumely also purchased the Gaar-Scott Company of Richmond, Indiana, the maker of the oldest steam engine tractor in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit. Both Advance and Gaar-Scott had long histories, developing steam engine tractors and other products for the agriculture market. In 1912, Rumely added Northwest Thresher Company, including Northwest’s 24-40 gasoline tractor. Rumely continued making the Northwest tractor as a 15-30, calling it the Gas Pull, until 1915.

Despite its recent acquisitions and its success with the new OilPull, the M. Rumely Company saw a drop in sales in 1913. After 2,656 OilPull sales in 1912, the company only had 858 OilPull sales in 1913, including Stuhr’s Type E 30-60. Having already borrowed money to acquire other firms, the company was in trouble. On January 1, 1914, Edward Rumely resigned from the company. At the end of 1914, the company had sold only 357 OilPulls. In January 1915, the M. Rumely Company filed bankruptcy and was appointed Finley Mount as its receiver. An Indianapolis lawyer, Mount trimmed off the company’s later acquisitions, leaving the company with the Rumely factory in La Porte and the Advance Thresher factory in Battle Creek. The company was renamed the Advance-Rumely Thresher Company and continued to do business without the Rumely family. Secor and Higgins continued as employees and made even more developments to their tractors.

It was at this time, during the late 1910s and early 1920s, that the company made Stuhr Museum’s Universal steam engine tractor, as well as its Types F, G, H, and K OilPull tractors. By 1924, with the popularity of smaller tractors increasing, Advance-Rumely needed to develop smaller tractors to compete with the Fordson and other tractor models. The company created the Types L, M, and R, and then Types W, X, and Z tractors, all smaller than their older brothers. By 1929, the company went even further, introducing the Do-All, an even smaller all-purpose tractor which is also represented in Stuhr’s exhibit. In 1930, Finley Mount and Edward Rumely, who had returned to the company after a failed stint in newspaper publishing, convinced Otto Falk, the head of Allis-Chalmers, to acquire Advance-Rumely. On June 1, 1931, Allis-Chalmers absorbed the company and became the fourth-largest farm equipment manufacturer in the U.S. After the acquisition, Advance-Rumely’s tractors came to an end as its factory inventories came to an end.

It was at this time, during the late 1910s and early 1920s, that the company made Stuhr Museum’s Universal steam engine tractor, as well as its Types F, G, H, and K OilPull tractors. By 1924, with the popularity of smaller tractors increasing, Advance-Rumely needed to develop smaller tractors to compete with the Fordson and other tractor models. The company created the Types L, M, and R, and then Types W, X, and Z tractors, all smaller than their older brothers. By 1929, the company went even further, introducing the Do-All, an even smaller all-purpose tractor which is also represented in Stuhr’s exhibit. In 1930, Finley Mount and Edward Rumely, who had returned to the company after a failed stint in newspaper publishing, convinced Otto Falk, the head of Allis-Chalmers, to acquire Advance-Rumely. On June 1, 1931, Allis-Chalmers absorbed the company and became the fourth-largest farm equipment manufacturer in the U.S. After the acquisition, Advance-Rumely’s tractors came to an end as its factory inventories came to an end.

Notes

The history of Meinrad Rumely's company is from Randy Leffingwell, The American Farm Tractor (St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Company, 2002), pp. 67-71.

You can find a serial number list for Rumely tractors by clicking or touching here.

You can access Tractordata.com's page for the Rumely Type E by clicking or touching here.

You can find a serial number list for Rumely tractors by clicking or touching here.

You can access Tractordata.com's page for the Rumely Type E by clicking or touching here.

1920 Rumely Type K 12-20 Tractor

This tractor (serial #13866) was built by the Advance-Rumely Thresher Company in La Porte, Indiana. Advance-Rumely produced 7,284 Type Ks from 1918 to 1924. Weighing about 6,430 pounds, the Type K was built with a 2-cylinder engine with 6" x 8" bore and stroke, and was rated at 560 RPM. The Type K's Nebraska Tractor Test was #10, performed from May 1st to May 21st, 1920. You can view the test results as a pdf by clicking or touching here.

The Advance-Rumely Thresher Company, the maker of five tractors and one steam engine in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit, had a long history before its incorporation in 1915. Its history can be traced back to Meinrad Rumely, a German immigrant to the United States in 1848. In that year, at the age of 25, Meinrad moved to Canton, Ohio, where his older brother, Jacob, lived. In 1850, he moved to nearby Massillon, Ohio, to join his brother, John, who was working for Russell & Company. Not long after moving to Massillon, Meinrad left for La Porte, Indiana, where he became a blacksmith in 1852. After his brother, John, joined him in La Porte, the two brothers created M. & J. Rumely Company. They made their first thresher by 1857 and their first steam stationary engine in 1861. Their products found a ready market.

In 1882, after adding portable and traction steam engines to their product lines, Meinrad bought out John’s portion of the company and renamed it M. Rumely Company. Meinrad’s company continued to grow during the last two decades of the 19th century, producing thousands of steam traction engines and other products. When Meinrad died on March 31, 1904, his two sons, William and Joseph, became the leaders of the company. Edward Rumely, Joseph’s son, also joined the company. By 1907, Edward took a leading role, guiding the company to even more products, especially to the development of a tractor that ran on a fuel other than steam. In 1907, he got in touch with John Secor, an engineer who had been experimenting with low-grade distillate fuels in internal-combustion engines. Meinrad had been familiar with Secor’s work in the 1880s, and Meinrad’s son, William, discussed Secor’s work with Edward as they talked about the work of Rudolf Diesel.

When Edward Rumely and John Secor discussed development of a tractor with an internal-combustion engine, Secor decided to join the company. When Secor joined Rumely so too did Secor’s nephew, William Higgins. Higgins, an inventor himself, had been working on a kerosene carburetor, patenting his invention with the help of his uncle. For a reported $213,000 in stock, Rumely obtained these two inventive minds and their patents. With the addition of Secor and Higgins, the company began working on what would become the famous OilPull series of tractors. After testing the first two-cylinder kerosene-fueled engines in 1909, the M. Rumely Company began production of their first OilPulls in 1910. Although the shop crew referred to the tractor as Kerosene Annie, Edward Rumely and his secretary came up with the name OilPull. On February 21, the La Porte factory finished the first OilPull, a Type B 25-45, weighing about 24,000 pounds. Before the end of the year, the factory had completed its first 100 OilPulls.

Building on the company’s continued success, Edward decided to expand through acquisition. In October 1911, Rumely bought the Advance Thresher Company of Battle Creek, Michigan. At about the same time, Rumely also purchased the Gaar-Scott Company of Richmond, Indiana, the maker of the oldest steam engine tractor in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit. Both Advance and Gaar-Scott had long histories, developing steam engine tractors and other products for the agriculture market. In 1912, Rumely added Northwest Thresher Company, including Northwest’s 24-40 gasoline tractor. Rumely continued making the Northwest tractor as a 15-30, calling it the Gas Pull, until 1915.

Despite its recent acquisitions and its success with the new OilPull, the M. Rumely Company saw a drop in sales in 1913. After 2,656 OilPull sales in 1912, the company only had 858 OilPull sales in 1913, including Stuhr’s Type E 30-60. Having already borrowed money to acquire other firms, the company was in trouble. On January 1, 1914, Edward Rumely resigned from the company. At the end of 1914, the company had sold only 357 OilPulls. In January 1915, the M. Rumely Company filed bankruptcy and was appointed Finley Mount as its receiver. An Indianapolis lawyer, Mount trimmed off the company’s later acquisitions, leaving the company with the Rumely factory in La Porte and the Advance Thresher factory in Battle Creek. The company was renamed the Advance-Rumely Thresher Company and continued to do business without the Rumely family. Secor and Higgins continued as employees and made even more developments to their tractors.

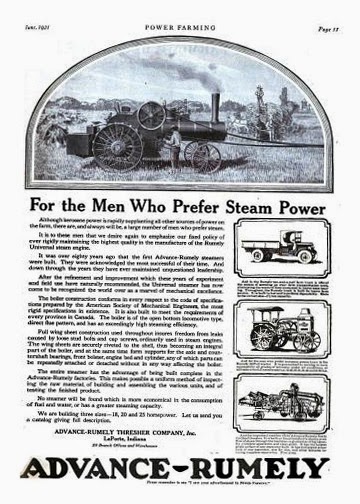

|

| From Power Farming, Vol. 30, No. 6 (June, 1921), p. 11. |

It was at this time, during the late 1910s and early 1920s, that the company made Stuhr Museum’s Universal steam engine tractor, as well as its Types F, G, H, and K OilPull tractors. By 1924, with the popularity of smaller tractors increasing, Advance-Rumely needed to develop smaller tractors to compete with the Fordson and other tractor models. The company created the Types L, M, and R, and then Types W, X, and Z tractors, all smaller than their older brothers. By 1929, the company went even further, introducing the Do-All, an even smaller all-purpose tractor which is also represented in Stuhr’s exhibit. In 1930, Finley Mount and Edward Rumely, who had returned to the company after a failed stint in newspaper publishing, convinced Otto Falk, the head of Allis-Chalmers, to acquire Advance-Rumely. On June 1, 1931, Allis-Chalmers absorbed the company and became the fourth-largest farm equipment manufacturer in the U.S. After the acquisition, Advance-Rumely’s tractors came to an end as its factory inventories came to an end.

Notes

The history of Advance-Rumely is from Randy Leffingwell, The American Farm Tractor (St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Company, 2002), pp. 67-71.

Information on Rumely tractors, and many other tractors, can be found at Tractordata.com. The page for the Rumely Type K can be accessed here.

Information on Rumely tractors, and many other tractors, can be found at Tractordata.com. The page for the Rumely Type K can be accessed here.

1928 Fairbanks-Morse Type Z 20 HP Engine

This 20 HP engine (serial #714769) was made by Fairbanks, Morse & Company of Chicago, Illinois. Fairbanks, Morse, & Company was created by Charles H. Morse, a very successful agent for the E. & T. Fairbanks Company of St. Johnsbury, Vermont. In 1850, Morse became an apprentice with the Fairbanks company, a company specializing in weighing scales. In 1857, Morse moved to Chicago where Fairbanks had a sales office. After the 1871 Chicago fire destroyed a large portion of the city, the smart and energetic Morse took over the Chicago office and started Fairbanks, Morse, & Company.

By 1880, Morse also became the sole agent for the Eclipse Wind Energy Company of Beloit, Wisconsin, using his developing connections to turn the Fairbanks-Morse Company into a major supplier of windmills to the railroads and to farmers. Later in the 1880s, Morse also gained control of Williams Engine Works of Beloit, obtaining a piece of the steam engine market. In 1893, Morse persuaded James A. Carter, an innovator of gas engines, to head a new gas engine department for the Fairbanks-Morse Company. Morse licensed several patents acquired by James and his brother, John, in the 1890s.

With connections to the railroad and to farmers via its windmills, the company sold many engines to railroad companies and farmers throughout the country. The company also established ties with the mining industry, creating another market for their engines. By 1895, Fairbanks, Morse & Company was making vertical and horizontal gas engines for a very wide market. During the next several decades, the company’s most popular engine series was the Type Z series, started in 1915, and represented by three different engines here in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit.

Notes

A brief history of Fairbanks, Morse & Company can be found in C. H. Wendel. American Gasoline Engines Since 1872. Edited by George H. Dammann. Sarasota, FL: Crestline Publishing Co., 1983.

c. 1910s Cushman Type C 4 HP Engine

|

| The Cushman Type C 4 HP Engine (serial #12659). |

This engine (serial #12659) was made by Cushman Motor Works in Lincoln, Nebraska. Established by Leslie S. and Everett B. Cushman, Cushman Motor Works began manufacturing 2-cycle marine engines at the beginning of the 20th century, obtaining patent 703695 in 1902, and patents 721287 and 736224 in 1903. In 1904 and 1905, the company converted the 2-cycle marine engines to stationary use. From 1904 to 1906, they added a 3 HP horizontal engine to their products, and in 1905, they added a vertical engine. In 1908, they started producing a 4-cycle vertical engine rated at 3 HP, which they made until 1910. Then, in 1910, they redesigned the 4-cycle vertical engine, which was rated at 4 HP, creating the model represented by the two Cushman engines in Stuhr Museum’s exhibit. The company often called this 4 HP engine a “binder engine,” seeing it especially as an engine for grain binders.

The box in front of the engine would have held the battery used for ignition; and the tank held water used for the cooling system. This engine has a 4” bore and stroke. The engine itself weighs about 190 pounds, while the entire outfit with tank, battery, and truck would weigh about 380 pounds. Cushman made the 4 HP engine until the 1930s, although the later models had an air cleaner and magneto. As late as 1934, a Cushman 4 HP engine with tank and battery cost $105.

|

| A Cushman ad from Farm.Implements,Vol. XXVIII, No. 12 (December 24, 1914), p.55. |

Notes

Information regarding Cushman's history can be found in C. H. Wendel, American Gasoline Engines Since 1872, edited by George H. Dammann (Sarasota, FL: Crestline Publishing Co., 1983), pp. 115-116.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)