(If you have read the web page for the Henney Surrey, most of the information below is repeated from that entry. Near the bottom of this entry, however, is some information on the Queen No. 2 heater found on the floor of this buggy.)

John W. Henney, Sr., the founder of the Illinois company that made this covered buggy and the nearby two-seated surrey, was born in Centre County, Pennsylvania in 1842, the son of Jacob Henney who was also a buggy maker. In 1854, John moved west with his family, settling in Cedarville, Illinois where his father set up a new buggy shop. John grew up around buggies, learning about the business not only from his father in Cedarville but also from other businessmen throughout the region. In 1864, as the railroads opened up the West to new settlers, John ventured out to Kansas City where he worked in the buggy trade for three years. By 1867, he found himself back in Cedarville taking over his father’s business, a local and not very successful enterprise according to an 1888 biography.1

John, however, had the energy and the desire to turn the business into something bigger. By 1876, he had succeeded in growing his company to the point where he needed to build a larger shop. At this time he also brought in his brother-in-law, Oliver P. Wright, as a partner. J. W. Henney & Company, as the business was called at this time, employed about fifteen to twenty men, and Henney became a locally known name. Wanting to expand business further, in 1879, Henney traveled around the region, visiting cities such as Dubuque, Iowa and establishing relationships with Mississippi River trading companies.

As his business continued to grow, Henney decided to move his shop from Cedarville to Freeport, a move which cut out about six miles of road travel each way and gave the company more immediate access to the nearest railroad. By 1880, the Freeport plant was making about 500 buggies and wagons a year. It was around this time that J. W. Henney & Company became the Henney Buggy Company, and Henney and Wright were joined by Daniel C. Stover, an inventor and founder of a local bicycle company, as stockholders. In 1883, as the company expanded production even more, five more men became stockholders. By 1887, the company was producing over 4,000 buggies and wagons in a year. Its growth was remarkable.

Before the turn of the century, however, the company ran into problems. On June 12, 1898, because of disputes within the ranks of the company, John Henney, Sr. quit. He stepped down from running the operation of the business; and, in 1900, he left Freeport to manage a Henney sales agency in Kansas City. In Henney's absence, Daniel Stover, one of the company's other stockholders, leased the company for five years beginning on November 3, 1898. During those five years, the Henney Buggy Company became the Henney Buggy Company, D. C. Stover & Company, and Proprietors. At first, the company continued to be strong, producing several thousand vehicles each year; however, by 1902, the Freeport company went into receivership.

Fortunately for the Freeport plant and its employees, the leaders of a nearby Moline, Illinois company came to the rescue. On October 2, 1902, the Moline Plow Company, known for its farm implements, entered into a contract with Stover to purchase all of Henney’s output from November 1, 1902 to July 1, 1903 and to market those vehicles through its head office, branches, and agencies. Going a step further, on June 3, 1903, the Moline company exercised an option to purchase the Henney company, its factory, patents, and machinery outright. Moline’s stockholders reorganized the company, taking over on July 20, 1903. In addition to reorganizing the company, Moline rehired John Henney, Sr., who had recently moved back to Freeport, as superintendent of the plant. Over the next few years, John returned the company to its successful past.

Around 1906, John W. Henney, Jr. entered the company; and by 1910, he had succeeded his father as superintendent of the Henney plant in Freeport. Under John, Jr.'s leadership, the Henney plant produced thousands of horse-drawn vehicles for markets throughout the United States. In 1911, despite the company’s continued success, John, Jr. resigned. Even without a Henney at the helm, the company continued to be successful, manufacturing thousands of vehicles over the next four years.

Although buggies continued to sell over those four years, it became apparent to the Moline company’s leaders that the automobile was quickly surpassing the buggy in popularity. Wanting to keep up with the changing times, in 1915, the Moline Plow Company ceased production of its many models of vehicles at the Freeport plant. By April, 1916, the company had shifted production from horse-drawn vehicles to the Stephens automobile; and, for the next eight years, the Freeport plant would make the Stephens.

The year 1915 marked the end of an era for the Henney factory. Over nearly five decades of buggy production, the Henney companies in Cedarville and Freeport manufactured over 200,000 vehicles. Henney's lines of vehicles grew just as the company's overall output grew. In 1893, John Henney, Sr.'s company advertised 26 different styles of horse-drawn vehicles. By 1896, the company had expanded to 49 different styles. In 1904, under the ownership of the Moline Plow Company, Henney advertised 53 different vehicle styles. And by 1914, even as the automobile was replacing the horse-drawn buggy on American roads, Moline advertised 98 different styles of vehicle made at the Henney Buggy Company plant.

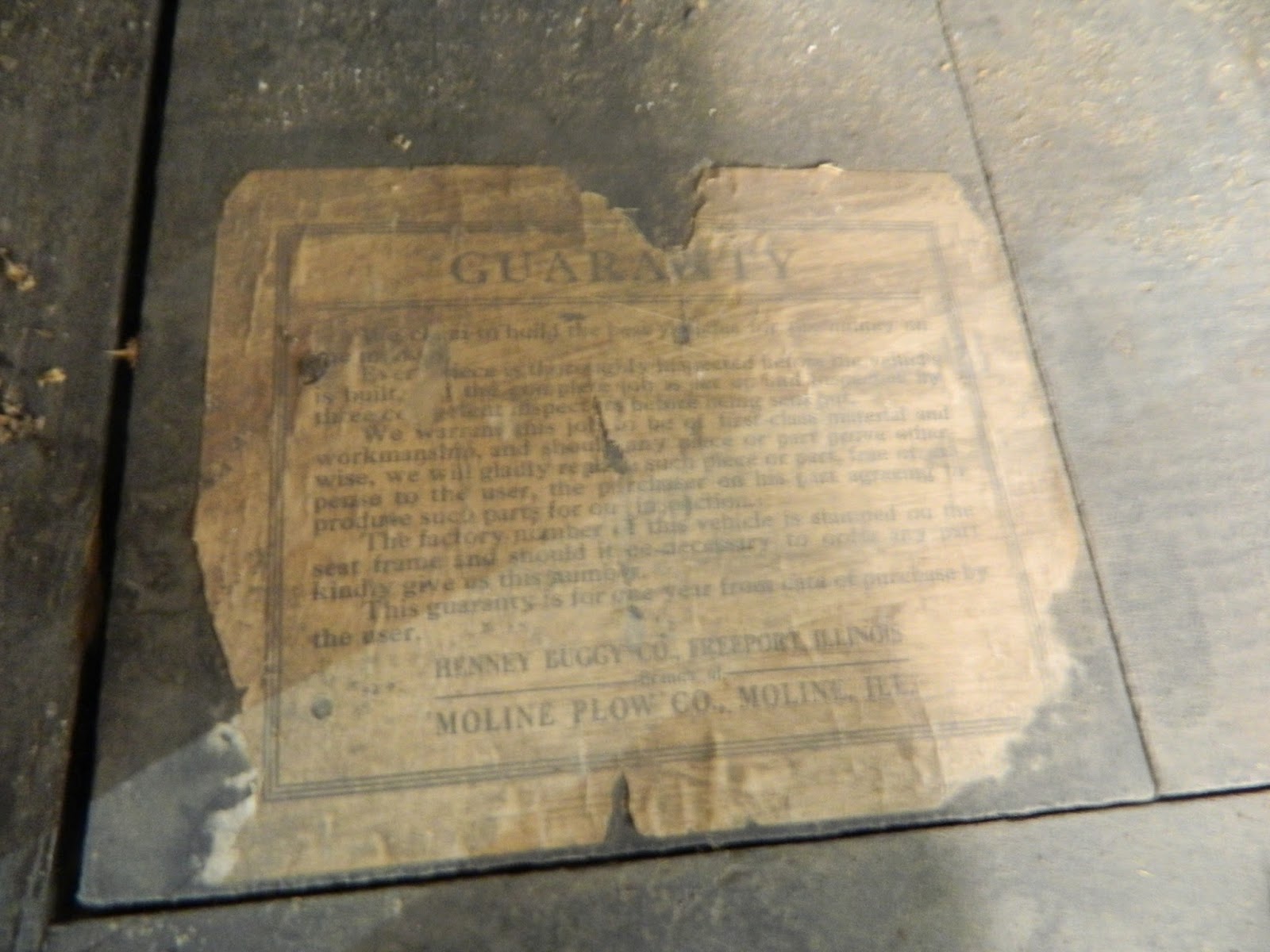

Even though the Henney factory in Freeport stopped making horse-drawn vehicles in 1915, many Henney vehicle owners continued to travel on their buggies, carriages, and wagons throughout the 1910s and beyond. Fortunately for those of us living nearly a century after the Freeport plant made this buggy, the Moline Plow Company placed a metal plaque on the back of this buggy as well as a paper one-year "guaranty" on the wood seat of this buggy. That guarantee (pictured above) and that metal plaque enable us to date this buggy to between 1903, when Moline acquired the Henney factory outright, and 1915, when Moline ended production of the Henney buggies.

Although you may not be able to see it from the walkway, this buggy has a foot heater on its floor in front of the seat. The heater is a “Queen No. 2” Heater made by the Lehman Brothers Company of New York, New York. It is about 14 inches long and has a drawer on one end. In order to use the heater, the rider would place a heated Lehman Coal into the drawer. The coal produced no smoke or smell, only heat. On cold trips, a buggy rider welcomed the heat from the buggy’s floor. A rider might even wrap a blanket around his or her body and around the heater to take advantage of the emanating warmth. An 1898 advertisement stated that a two-cent coal could provide eight hours of heat.

|

From Hardware Dealers Magazine, vol. XXV, no. 1

(January, 1906). |

Notes

1 The early part of Henney’s history, especially as it revolved around John W. Henney, Sr. is from Portrait and Biographical Album of Stephenson County, Ill., Containing Full Page Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens of the County, Together with Portraits and Biographies of All the Governors of Illinois, and of the Presidents of the United States (Chicago: Chapman Brothers, 1888), pp. 468-470. The remainder of the history here comes from Thomas A. McPherson, The Henney Motor Company: A Complete History (Hudson, WI: Iconografix, 2009), pp. 10-26. After leaving the buggy factory in 1911, John Henney, Jr. moved to Chicago. With the help of his father and other partners, John, Jr. started another company in Freeport in 1915, making bodies for funeral coaches, buses, and ambulances. By the mid-1920s, Henney began making bodies for cars; and, when Moline stopped producing the Stephens and closed the old Henney plant in Freeport in 1924, John, Jr. purchased the plant and moved his newer business into the former Henney Buggy Company facilities. In 1927, Henney reorganized and renamed his company the Henney Motor Company. It would become a very successful enterprise, remaining in business until the 1950s.